Indigenous Peoples

For around 8500 years, ever since glaciers retreated after the last ice age, Mount Tahoma has provided physical and spiritual nourishment for the people who live around her. This mountain looms large in the history, culture, and myth of the region.

Disclaimer: I've done my best to accurately gather and vet the information that follows, but sources are incomplete and often contradictory. Please let me know any corrections.

Visitation

Indigenous people used the upper and lower parts of the mountain very differently. Above the spirit line, which was roughly the permanent snowline around 7000' elevation, was a powerful and otherworldly realm. Visits to such rarified places were few and significant, part of guardian spirit quests that required ritual preparation and could grant profound spirit knowledge.

Below the snowline, the high meadows were an important food source for several tribes. Small groups would travel from as far away as the Salish Sea (Puget Sound) to visit for a week or two in late August or early September. The primary purpose was for the women to gather huge quantities of huckleberries for winter supplies. Meanwhile the men hunted deer, elk, bear, mountain goats (which were notoriously challenging due to their precarious and high altitude habitat), marmots (for fat and fur), and grouse. Secondary activities included collecting pine nuts and bear grass, which was used in weaving baskets.

Both berries and meat were dried to preserve them through the winter. The antimicrobial properties of cedar containers kept berries from spoiling before they could be dried over smoking fires on cedar bark mats. Meat was cut in pieces and hung on wooden frames with fires built on three sides to roast it, then moved higher to dry more slowly. Bear meat was sometimes steamed in a pit with hot rocks rolled in to form a floor, the meat placed on a rack of branches, covered with more branches and a few inches of dirt, then water poured in to create steam.

There were no permanent settlements inside what is now Mount Rainier National Park. Temporary shelters consisted of lean-tos or conical tipis made from of a frame of poles that were tied together at the top and covered with tule mats or skins. Little archeological evidence remains due to the temporary visits and dynamic nature of the landscape, but arrowheads have been found on peaks in the Tatoosh Range, Van Trump Park, the upper slopes of Spray Park, and as high as 7500' on the Success Divide.

Fires were sometimes intentionally set before leaving at the end of the season. This maintained habitat by keeping down the brush, boosting berry production for the next year and making deer easier to hunt.

Tribal Identities

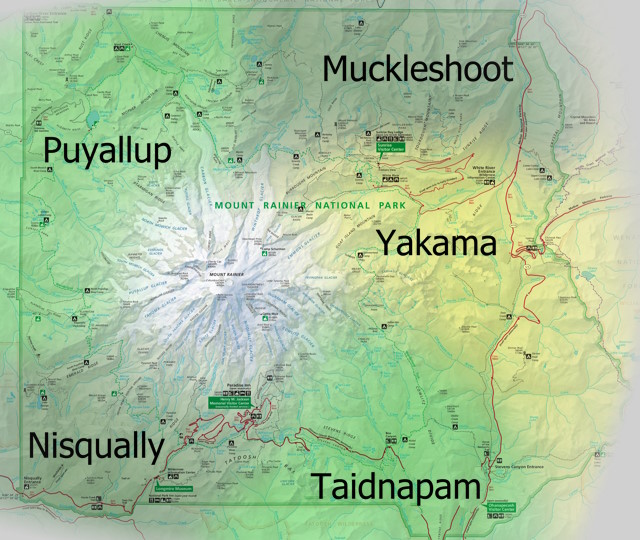

To the west and north of Tahoma were the Coast Salish tribes: the Nisqually, Puyallup, and Muckleshoot. They spoke Lushootseed, often travelled by dugout canoe, and lived near navigable water in villages of cedar longhouses. Salish society was complex and hierarchical but there was little political organization beyond the individual village. Closest to the mountain, the Nisqually had permanent villages near what are now Eatonville and Elbe, the Puyallup near modern Orting, and the Muckleshoot around Buckley and Enumclaw.

East of the Cascade Crest were the migratory plateau tribes: Yakama, Kittitas, and Klickitat. They spoke Sahaptin and rode horses. The Yakama crossed mountain passes to visit the eastern flanks of Tahoma, which provided resources not available in their sagebrush country further east.

Combining elements of both cultures were the Taidnapam, also known as Upper Cowlitz or Cowlitz Klickitat. They lived in permanent villages along the Cowlitz River, including the area now called Packwood, but spoke Sahaptin and had close ties to the Yakama. Taidnapam / Upper Cowlitz are culturally distinct from the Lower Cowlitz, who are a Coast Salish tribe.

Many sources use tribal labels imprecisely, for instance referring to the Taidnapam simply as Cowlitz, or grouping the Sahaptin-speaking Yakama and Taidnapam tribes under the label Klickitat. I suspect this is partly due to the carelessness of early writers, but it is important to recognize that distinct separation of tribes was an outside concept imposed during treaty negotiations. Culture and language varied continuously without clear breaks. Neighboring but autonomous villages were closely related through intermarriage and trading, with especially strong ties within each watershed. The culture was cosmopolitan and many individuals (even some whole villages, especially those closer to the mountain) were bilingual in Lushootseed and Sahaptin.

Mythology

In the age before time began, elements of today's landscape were once people who moved around, loved and fought with each other. Tahoma is usually but not always female in these tales (she's definitely female in my own headcanon).

Tahoma, sent away, with son on her hip |

In Nisqually and Puyallup myth, Tahoma once lived with other peaks in the Olympic Mountains, but the others decided there was no room for her there. Sent away along with her son, she reminded him to bring water for the journey. Tahoma carried her son (Little Tahoma) on her hip to the place where they sit today. He did indeed remember to bring water, hence the many streams that flow from the mountain.

Duh-hwahk gazing back at Kulshan |

Far to the north, the Lummi (a Coast Salish tribe from the Bellingham area) tell how Duh-hwahk (Mount Rainier) was married to Kulshan (Mount Baker) but became jealous when Kulshan's affections were stolen by Whaht-kway (Spieden Island), who was less beautiful but gentle and kind. Duh-hwahk packed her things, left her husband and three children, and travelled far to the south before settling in her current location, where she stretched high to see over the intervening hills and gaze longingly back at those she had left behind.

I have heard, but cannot attribute the origin, that when clouds roll in so Tahoma is not visible it means she has gone on vacation, visiting with her ex-husband or other loved ones in some distant place.

Legend needs updating: more recently it is Lawetlat'la that has lost her head! |

In other stories peaks engaged in battle, throwing fire and rocks at each other. According to a Cowlitz legend, Tahoma (this time male) once quarreled with his wives Lawetlat'la (Mount St. Helens) and Pahto (Mount Adams). Lawetlat'la became jealous, blew her top, and knocked the head right off of Tahoma.

Another Cowlitz tale explains why there are no snakes on Tahoma (ed: not strictly true). Tyee Sahale once told a wise man to shoot an arrow into the cloud that hung low over the mountain, where it stuck fast. The man then shot more arrows into that first arrow, making a chain up which he, his family, and all the good animals could climb. The bad animals were starting to follow after them, but the man broke the chain of arrows just as it began to rain. The land was flooded all the way up to the snowline of Tahoma. By the time it stopped raining and the waters receded, all the bad animals had drowned. This is why there are no snakes or other bad animals on Tahoma.

The Puyallup have several stories describing lahars (volcanic mudflows). One tells how there was once a vast lake in the valley between what is now Sumner and Renton, at which time the Puyallup River followed a different course than today. Two whales lived in the lake, but one day they became restless, thrashing about and churning up the water. They plowed into the land and forced their way through, opening a channel from the plain out into the sea. The water followed the whales and a new river came into being.

In another Puyallup story, a young man once climbed Tahoma in search of spirit power. On the top he found a lake in which he swam and washed himself, thus gaining magic. Tahoma told him he would live so long that moss would grow over him and his hair would fall out, and that when he eventually died of old age her head would burst open and the water in which he swam would rush down the hillside. And this is exactly what happened. The young man grew old, and after he died water burst from the head of Tahoma, swept the trees from the valley where Orting now is, and left the prairie covered with stones.

Placenames

The Nisqually, Puyallup, and Cowlitz tribes share their names with the rivers where they lived, which are also the names of the glaciers that feed these rivers and of various adjacent geographic features (Cowlitz Divide, Puyallup Cleaver, etc.) It is meaningless to ask which of "people who live along the Nisqually River" or "river inhabited by the Nisqually people" came first.

The Yakima Park area (now known as Sunrise) is named after the Yakama tribe.

The Sahaptin language of the Yakama and Taidnapam contributed some of my favorite poetic names:

- Naches means 'turbulent water'

- Ohanapecosh means 'standing at the edge' (this was the name of a Taidnapam settlement a few miles outside the current National Park boundary)

- Wauhaukaupauken means 'spouting water'

- Wow means 'goat' (demonstrating the geographic overlap of languages, as Mount Wow is located well within the territory of the Salish-speaking Nisqually tribe)

The Lushootseed language of the Puget Sound Salish gave us:

Kiya Lake used to be named after a racist label for Native women, before the Department of the Interior finally got around to declaring Sq___ a derogatory term in 2022. While we're at it, can we please find more respectful new names for Indian Bar and Indian Henry's Hunting Grounds?

The Chinook Jargon was a pidgin trade language with some aspects of a creole, partially based on the Chinook language from the lower Columbia River plus elements of other tribal languages, French, and English loanwords. During the 19th century it spread as far as Northern California, Alaska, and Montana. It was the source of many Tahoma placenames:

- Alki means 'by and by'

- Ipsut means 'concealed' (perhaps due to the tucked away location of Ipsut Falls)

- Kotsuck means 'middle'

- Mowich means 'deer' (because from this angle the rock and ice high on the mountain somewhat resembles a deer's head)

- Olallie means 'berry'

- Tamanos means 'guardian spirit'

- Tatoosh means 'nourishing breast'

- Tenas means 'little'

- Tipsoo means 'grassy, hairy'

- Tyee means 'chief, gentleman, officer'

There are also some places named after individuals:

- Owyhigh Lakes are named after Chief Owhi of the Yakama.

- Satulick Mountain and the meadows known as Indian Henry's Hunting Grounds are named after So-to-lick, aka Indian Henry, a Taidnapam/Yakama farmer and guide who hunted in this area.

- Sluiskin Falls is named after a Taidnapam guide from the first documented ascent of Tahoma in 1870.

- Wahpenayo Peak is named after a chief who was related to So-to-lick by marriage.

- Wapowety Cleaver is named after the Nisqually guide of an unsuccessful 1857 summit attempt.

Erasure

Through much of the 20th century the long relationship of Native tribes with Mount Tahoma was rounded down to near zero.

Evidence of rare but spiritually significant visits to the upper mountain was discounted because the Very Brave and Intrepid Explorers of this Untrammeled Wilderness with all their To Boldly Go energy had to be truly the first there, amiright? Let none question why the very same people who wrote how Indians were too scared to climb high on the mountain were finding the guide services of So-to-lick so very valuable. When Sluiskin was hired to guide the First Ever Summit Ascent and he warned of dangers including a lake of fire on the summit, this was discounted as primitive superstition because, well, lake of fire on top of a volcano? What a ridiculous thing to say :-)

Restoring access: parts of the Stewardship Campground at Longmire are now reserved for use of the Nisqually Tribe |

After the 1899 creation of the National Park, erasure broadened to an insistence that even the lower mountain had never been much used by Native people. This fabrication avoided conflict with treaties such as the one maintaining Yakama rights to hunt, fish, and gather roots and berries. In the words of Cowlitz tribal member Bill Iyall:

"If the government wanted to set aside land, they'd say Indian people never used it. Actually there was a lot of practical use of Mount Rainier - for food and for fun; for family. But the general attitude of the time was that Indians didn't live there. Reports refer to the tribal presence as 'visitors'. But Indian people lived there, just not all the time."

By combining physical evidence with oral histories, more recent anthropology is starting to fill the gaps in this record.

Tahoma vs. Rainier

Spellings and pronunciation varied, but all the surrounding tribes more or less agreed on the name of the mountain. Various sources give the names:

- Nisqually: Tahoma, Taqoma, or Tkobed

- Puyallup: Tahoma or Takhoma

- Muckleshoot: Taqobid

- Yakama: Tahoma, Takhoma or Taxoma

- Taidnapam: Takhoma

More generally, Tahoma means 'snowy mountain' and can refer to any snow covered peak. This linguistic structure is familiar to current residents of Seattle, who universally understand the difference of meaning between 'mountain' and 'The Mountain'.

Naming controversy began in 1873 when a young sawmill town called Tacoma was selected as the terminus of the Northern Pacific Railroad. An influx of railroad money smelled a marketing opportunity to rename Mount Rainier and have it match their new town, but newspapers and businesses in rival Seattle raised objections:

- We can't violate the longstanding principle that the first white man to see something gets to name it for perpetuity.

- Who even knows what Native people called the mountain? So many different tribes and spellings...

- Tacoma could refer to any snowy mountain, not always specifically Rainier.

- Native people never visted the mountain much anyway...

The debate continued past a pro-Rainier 1890 ruling by the US Board of Geographic Names. Teddy Roosevelt chimed in favoring an indigenous name, and in 1917 the state legislature passed a resolution to rename, but the effort stalled. Perhaps conditions are ripe for another try soon?